[Summer 2024 GPS] Why Dividends Are Overrated

James Schofield - Aug 16, 2024

You might not want to make investment decisions based solely on a company's dividend yield. Warren Buffet's Berkshire Hathaway doesn't pay a dividend, and it's share price has increased by over 3 million percent in the past 60 odd years! Why?

Many investors make the mistake of believing that the dividends a company pays are the equivalent of free money. The reality is that dividends decrease the profit of a company dollar for dollar and in turn, make the company less valuable. Before we delve into why dividends do not create value for investors, lets back up a few steps. Companies generate revenue based on selling their products and services to customers and have ongoing expenses like salaries, research & development and equipment to name a few. When a company has money left over after paying its current expenses, it has many options, such as paying down debt, repurchasing shares, making strategic acquisitions, expanding operations, or paying a dividend. Paying a dividend is the least tax-efficient use of capital. Why? Because when a company pays a dividend to its shareholders, it must pay tax on that income at the corporate level, and the shareholder will also have to pay tax on this income at the personal level. In contrast, when a company uses it's earnings to pay down its debt, it retains the amount that would have been used to pay taxes at the individual shareholder level, therefore allowing it to retain more of its profits after corporate taxes are paid. All the other potential uses of the company's profits share that same feature. Paying dividends is a decision that companies evaluate against other potential uses of their capital. The fact that a company pays a dividend instead of using their profit in other ways can be an indication that the company doesn’t think it can use its capital to generate an adequate return on investment.

Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway does not pay a dividend reasoning that the free cash that would be used to pay a dividend can instead reinvested in the company to improve efficiency, expand their reach, and create new products and services or improve existing ones. Based on the company's performance, Buffett has made the right choice as shares of Berkshire Hatheway have increased by 3,787,464% from 1965 to 2022 compared to the S&P 500 returning 24,708%[i]. Buffett isn't the only successful CEO who feels there are better uses of his company's free cash flow than paying dividends. Constellation software is one of the best performing Canadian stocks over the last 10 years and their chairman Mark Leonard has resisted paying dividends along the way. Like Buffett, Leonard believes Constellation can earn a better rate of return investing their free-cash flow back into the business, delivering much more value to shareholders[ii]. To be clear, we are not suggesting that there is anything wrong with companies that do pay a dividend, many successful companies have paid dividends for a long time and will continue to do so while creating value for their shareholders. We suggest that making investment decisions solely based on the stock's dividend yield could be a recipe for underperformance.

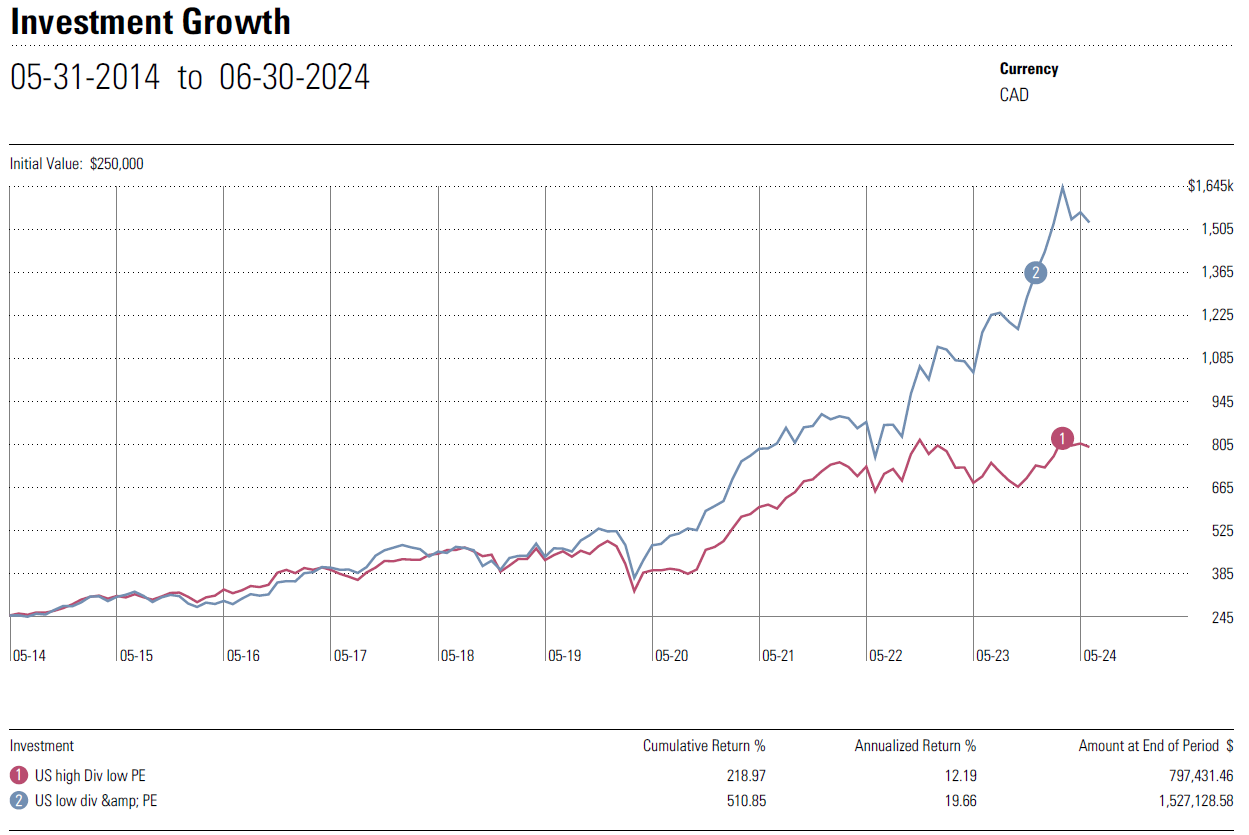

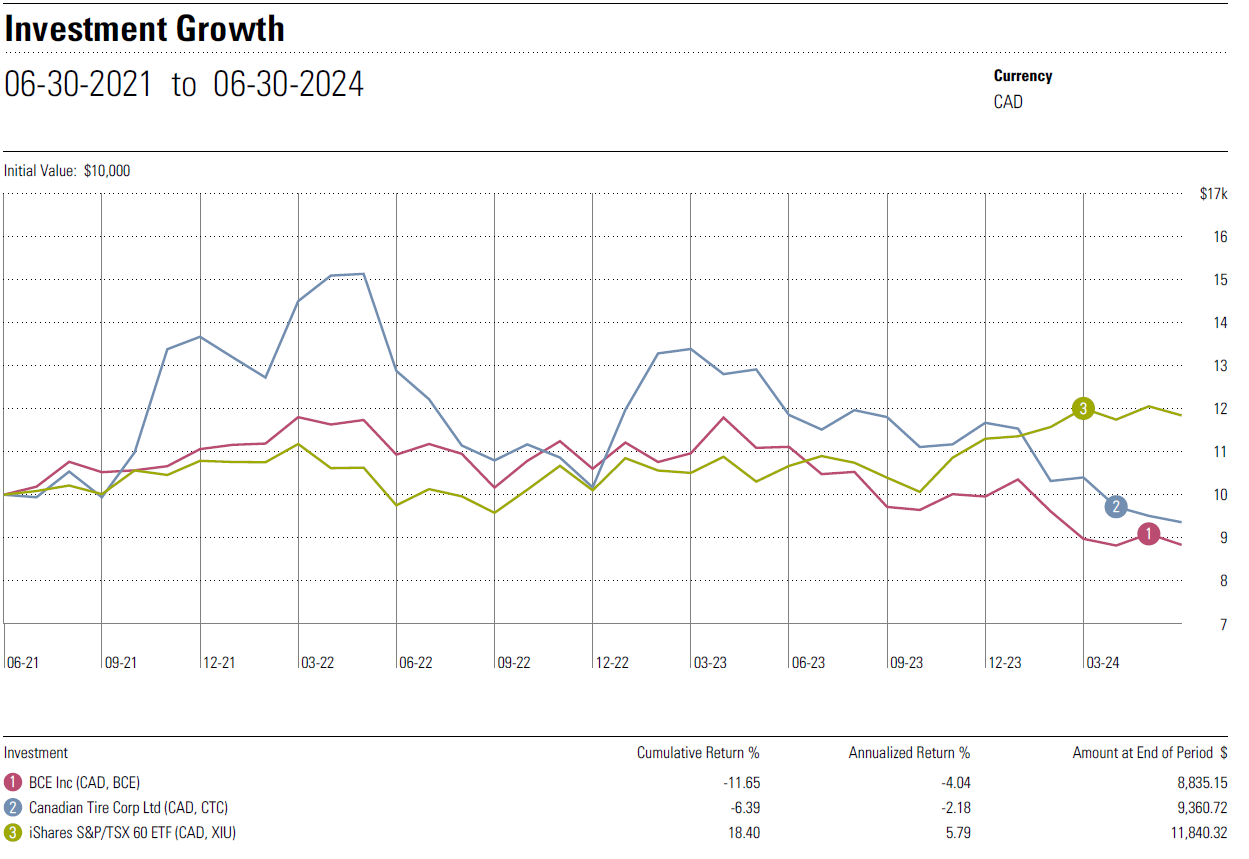

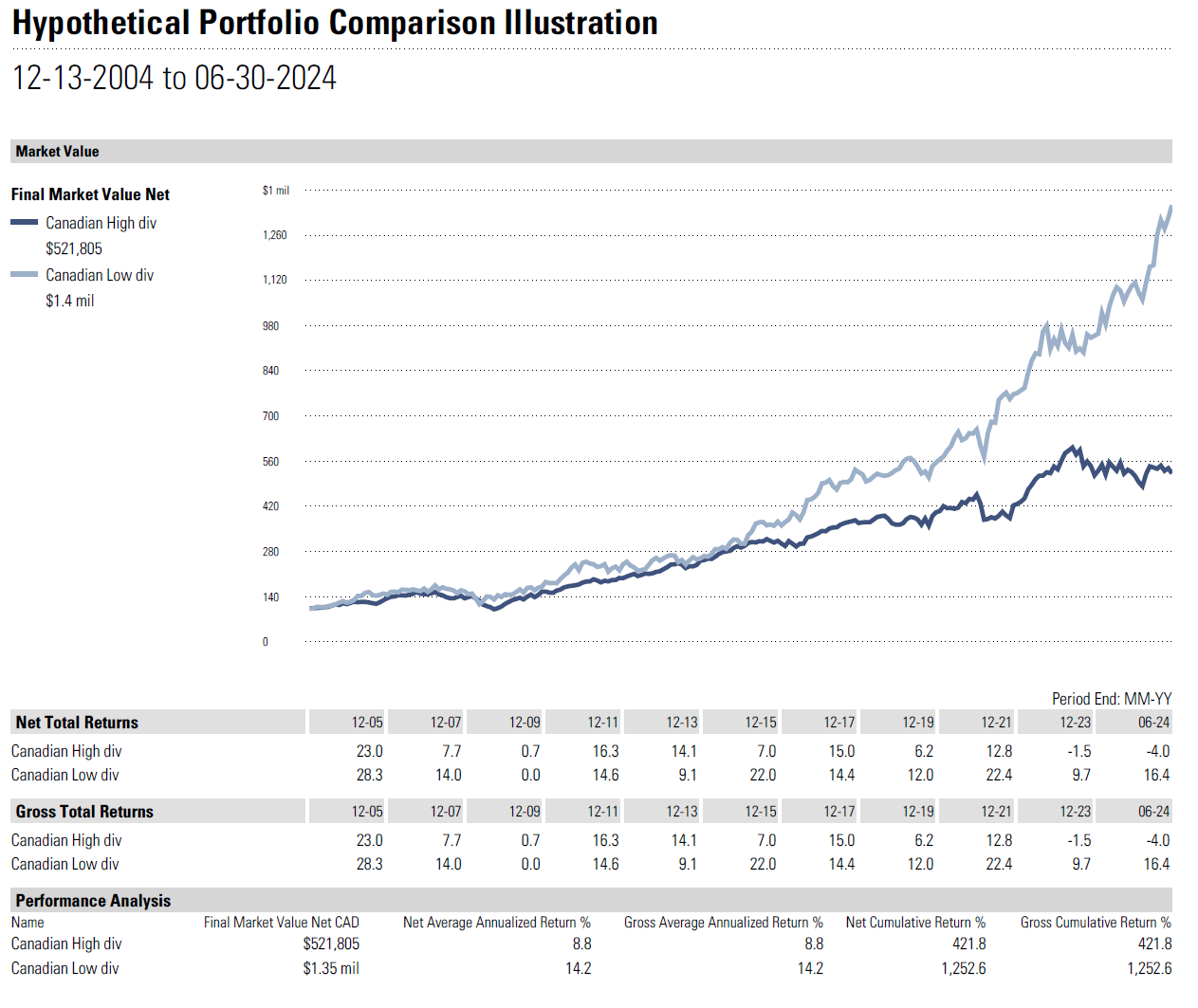

Dividends can be a signal that a company is consistently profitable and can afford to pay dividends to its shareholders without sacrificing its future financial health. However, a growing dividend payout ratio (dividend per share divided by earnings per share), can be a signal that a company's profits are not growing at the same rate as it's dividend yield and can be a sign of trouble ahead. Dividends are far from guaranteed and there are many examples of companies running into problems that force them to cut their dividend following steep decreases in their share prices. Algonquin Power is a recent example in Canada; when they went through financial struggles in late 2022, they cut their dividend by almost half. Other companies have conditioned their investors to expect consistent increases to their dividend and have maintained paying it even during less prosperous periods. Two examples in Canada are Bell and Canadian Tire. Both companies have increased their dividend even through periods of declining earnings growth. Though some investors no doubt appreciate receiving their growing dividend cheque, others will notice that the share price decline has eaten away at their overall returns. Bell's 3-year annualized return is -3.21% including dividends, while Canadian Tire's 3-year return is -1.71% compared to the S&P/TSX 60 which has returned 6.61% over the same period.[iii] We acknowledge that this is a small sample size, so we looked at the largest 23 stocks on the TSX and compared the 11 with the highest dividend yield to the 12 with the lowest dividend yield on performance from 2004 to 2024. The high dividend group returned 8.8% while the low dividend group returned 14.2%.[iv] Concerned that this sample was still too small we looked at large US companies with dividend yields between 4 and 5% and compared these to similar sized companies with dividend yield between 1 and 2%. The high dividend group had respectable ten-year annualized returns of 10.48% whereas the low dividend group nearly doubled that return with 20.85%. Savvy investors might argue that the last 10 years have been abnormally favorable for growth vs. value as an investing style. To control for this recency bias we screened for companies with a price to earnings ratios below 15 for the high and low dividend groups, to ensure our sample only included "value stocks". A similar gap in returns persisted with the former generating an annualized 12.19% while the latter turned in a 19.66%.[v]

Another often overlooked feature of dividends is that they are generally less tax-efficient for the end investor. $100 in Canadian dividend income is grossed up by 38% when you file your taxes meaning that for a retiree in the 30% tax bracket, $100 in dividend creates $20 of additional taxes payable vs. $15 in additional taxes if the same $100 was earned as a capital gain. For retirees concerned about OAS clawbacks, the dividend income after the 38% gross up is used to calculate net income meaning the gross up can push taxpayers into OAS clawback range, which essentially amounts to an additional 15% tax.

Dividends are neither good or bad in and of themselves, the key message that we hope to get across in this article is that dividends are not free money. They are simply a capital allocation decision made by a company's leadership. Though the presence of a consistent dividend can be an indicator of financial health, you should not make investment decisions based on a company's dividend yield alone.

[i] https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/021615/why-doesnt-berkshire-hathaway-pay-dividend.asp

[ii] https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/rob-magazine/the-most-successful-canadian-dealmaker-youve-never-heard-of-and-will-never-see/article18134950/

[iii] Chart Source: Morningstar Advisor Work Station

[iv] Source: Morningstar Advisor Work Station

[v] Source: Morningstar Work Station