Is the U.S. Print-To-Pay Policy Coming to an End?

Alfred Lam - 31 mai 2023

All eyes are on Congress as the U.S. debt ceiling deadline creeps closer. Let's explore how the U.S. got to this critical point and the available options to avoid default.

Is the U.S. Print-To-Pay Policy Coming to an End?

In our lives, we often deal with uncertainties. Some are “known unknowns”, meaning we were aware of the event/issue but uncertain about the outcome; some are “unknown unknowns”, meaning no one saw it coming, it was sudden and random, like the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020. Today, the news is focused on the U.S. debt ceiling, which falls squarely in the “known unknown” category as it’s an issue that has been building for years. Intuitively, the U.S. government should not be allowed to default, and their borrowing limit should be increased such that bills are paid and Americans’ lifestyles can be maintained.

A History of Deficit

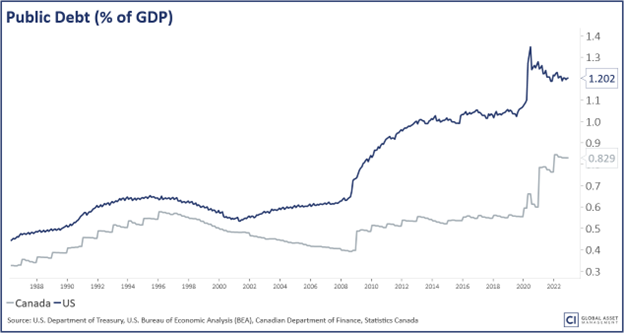

The reality is the debt ceiling was created for good reason. At the least it serves to ensure the government is sensible about its spending and debt level. To put debt in context, debt-to-GDP is a more sensible measure as debt is compared to the economy which ultimately correlates to potential tax that the government collects. As the chart above illustrates, U.S. debt-to-GDP has been growing and was 120% as of Dec 31, 2022; comparatively, the Canadian government has been more responsible with borrowing as its ratio was “only” 83%.

As you are aware, the U.S. economy has been growing at a rapid rate (partly due to inflation) with unemployment also at a decades-low level, meaning there are more taxpayers than normal, hence revenue for the government is above trend. Even then, the government is running an annual deficit. Is the U.S. deficit temporary? Unlikely, as mandatory spending accounts for almost all of the tax revenue, leaving some discretionary spending and interest payments to be paid via additional borrowing. If the situation is applied to a business or individual, they are unlikely to get new funding. Governments, however, have two powerful tools: taxing and printing money. For many reasons, it is unpopular to raise tax. The alternative, printing money, has led the U.S. Federal Reserve balance sheet to expand from less than $1 trillion 15 years ago to now over $8 trillion through purchases of U.S. sovereign bonds. During the same period, U.S. debt has nearly tripled. As the government spends more than it collects in taxes, it issues bonds to raise revenue. Some of the bonds are bought by private investors and a lot were actually bought by the Fed. In summary, the U.S. government funds itself through its agent, the Fed, which actually has no assets to begin with.

Results May Vary

It seems printing money solves all issues, including the latest banking crisis. Depositors had a run on several U.S. regional banks in March and April as they were concerned about the health of some banks and wanted to get paid back immediately. The “crisis” ended with the U.S. Treasury and the Fed expressing their intent to guarantee all deposits. No one doubted their ability to follow through on this as they own the privilege to print.

So, does printing money solve all issues? The answer is no. Based on past experiences, it has led to two outcomes. Following a large amount of printing in 2009 to fix the global financial crisis, the U.S. economy had years of sluggish growth and an unequal distribution of wealth. Recently, following very aggressive printing to offset the economic impact of COVID-19, we have had a period of very high inflation. There could be a third outcome if the U.S. government continues this route of print-to-pay, rather than earn-to-pay or spend less: investors could lose confidence in the U.S. monetary system, U.S. sovereign bonds, and the U.S. dollar. At the moment, it is a low probability event, but still possible.

The current event, the U.S. debt ceiling debate, will likely be resolved at the final hour, which is expected to be sometime in June when the U.S. government runs out of borrowing capacity. In U.S. history, asking for a raise is not uncommon. As the size of an economy grows, it is sensible to grow its borrowing capacity. That principle requires little debate. The problem this time is the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio has been high and rising since 2008. The last few U.S. presidents made no effort to address this. U.S. President Joe Biden insists the raise must be unconditional. As a lender, would you want to lend to someone who has no plans to fix a budget deficit?

Pros and Cons

If Congress does not approve a raise, the U.S. may still pay its debt as it is critical to maintain its credit rating and financial stability. However, civil servants may not get paid and social benefits may be suspended, at least for some time. This will create dramatic challenges to Americans’ lifestyles and have an immediate negative impact on the U.S. economy and stock valuations, and in turn lower U.S. tax revenue. Consequently, growing deficit and debt. If the debt ceiling is raised without conditions, the immediate response will probably be positive as it means the “party” continues. However, as we mentioned, this strategy carries the risk of loss of confidence in the system. It will take time to fully play out, and the damage may filter through very slowly. Investors should be mindful about this debt ceiling event, but not over-react.

Summary

After decades of overspending, the U.S. has hit its debt ceiling yet again and is on the brink of default. In the past, they’ve avoided addressing deficit issues by raising or suspending the debt ceiling and expanding the Federal Reserve balance sheet by issuing bonds and printing money. Yet, the outcome has been sluggish growth, inflation, and ever-increasing debt. Now, the options are to persist in the same cycle, potentially dissolving confidence in the U.S. monetary system, or allow a default that would have widespread implications.

About the Author

Alfred Lam

Alfred Lam, Senior Vice President, Co-Head of Multi-Asset, joined CI GAM in 2004. He brings over 23 years of industry experience to his portfolio design, asset allocation, portfolio construction, and risk management responsibilities, which include chairing the multi-asset investment management committee and sizing investment bets to drive added value and manage risk. Alfred holds the CFA designation and an MBA from York University Schulich School of Business. He is a recognized leader in multi-asset investing in Canada. During his tenure, his team has won multiple investment awards, including the Morningstar Best Fund of Funds, and saw assets growing four-fold.